Alummoottil and the British: A Complex Chapter in Onattukara’s History

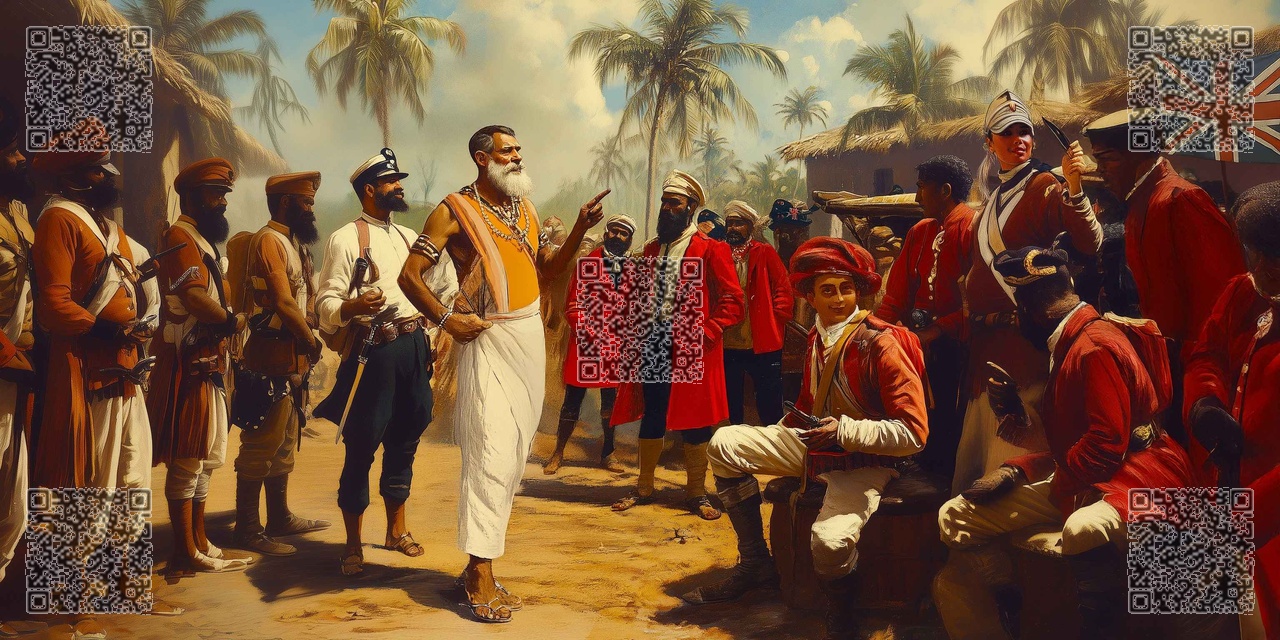

The Alummoottil family, renowned for their martial heritage and vast agrarian wealth, navigated a tumultuous relationship with the British presence in Travancore throughout much of the 19th century. At its core, this bond was defined by mutual suspicion: the British saw in the Alummoottils both a potential ally and a formidable threat, while the Alummoottil chieftains viewed the foreign power as a force disrupting their ancestral way of life.

Central to the conflict were the British attempts to control or abolish Kalari practices—martial art schools that had long been part of Alummoottil tradition. Concerned about potential armed resistance, the British administration in Travancore sought to curtail the influence of these kalaris under various pretexts, including law and order. Yet, even as they tried to ban the martial schools, British officers occasionally relied on the Alummoottils for local security or intelligence, showing rare moments of cooperation when it suited their immediate interests.

Economic tensions also fueled the discord. The Alummoottil family’s substantial wealth—bolstered by agricultural holdings, livestock, and trade connections—made them frequent targets of British extortionate practices. Some British officials, eager to increase revenue, levied heavy taxes or imposed fines under dubious legal grounds. These taxes struck at the heart of the Alummoottil estate, threatening not only the family’s wealth but also their socio-political influence in Onattukara.

However, diplomacy intermittently eased these strains. Depending on who served as the Diwan of Travancore, policies toward indigenous elites could shift significantly. Certain diwans and British Residents displayed an understanding of local customs, choosing negotiation over force. In those periods, the Alummoottil chieftains maintained guarded friendships with British officers stationed at the Travancore cantonment. During cordial phases, the Alummoottils were sometimes invited to official gatherings, and ceremonial gifts were exchanged to symbolize a temporary detente.

Yet these friendly intervals were short-lived. In 1875, one of the most notable incidents occurred: the British seized 250 cows belonging to the Alummoottil family, ostensibly as payment for alleged arrears. The action provoked a fierce response. The Alummoottil chieftains, already aggrieved by years of tax hikes and martial restrictions, rallied their retainers to confront the British detachment. Although the confrontation ended with the return of some of the cattle after protracted negotiations, it left a deep scar on local sentiments.

Another major altercation followed when the British, in an effort to strong-arm the family further, deliberately allowed saline water to flood the Alummoottil paddy fields. The brackish influx devastated the year’s crop and rendered portions of the land unsuitable for cultivation for several seasons. This act, seen by the Alummoottils as sheer vindictiveness, was later criticized even within some British administrative circles for its destructive impact on regional food supplies.

These episodes, emblematic of a cycle of hostility and reluctant cooperation, underscored the precarious balance the Alummoottil family strove to maintain. On one hand, they had to preserve their martial traditions and economic might. On the other, they needed to navigate the ever-shifting policies of an intrusive British administration. By the close of the 19th century, while the British grip on the region tightened, the Alummoottils remained resilient—determined to protect their heritage in the face of an empire that alternated between alliances of convenience and campaigns of repression.