(Diwan Krishnan Nair was NOT a member of the Alummoottil Family. However, he enjoyed very close ties with our family, and has significantly influenced our family history)

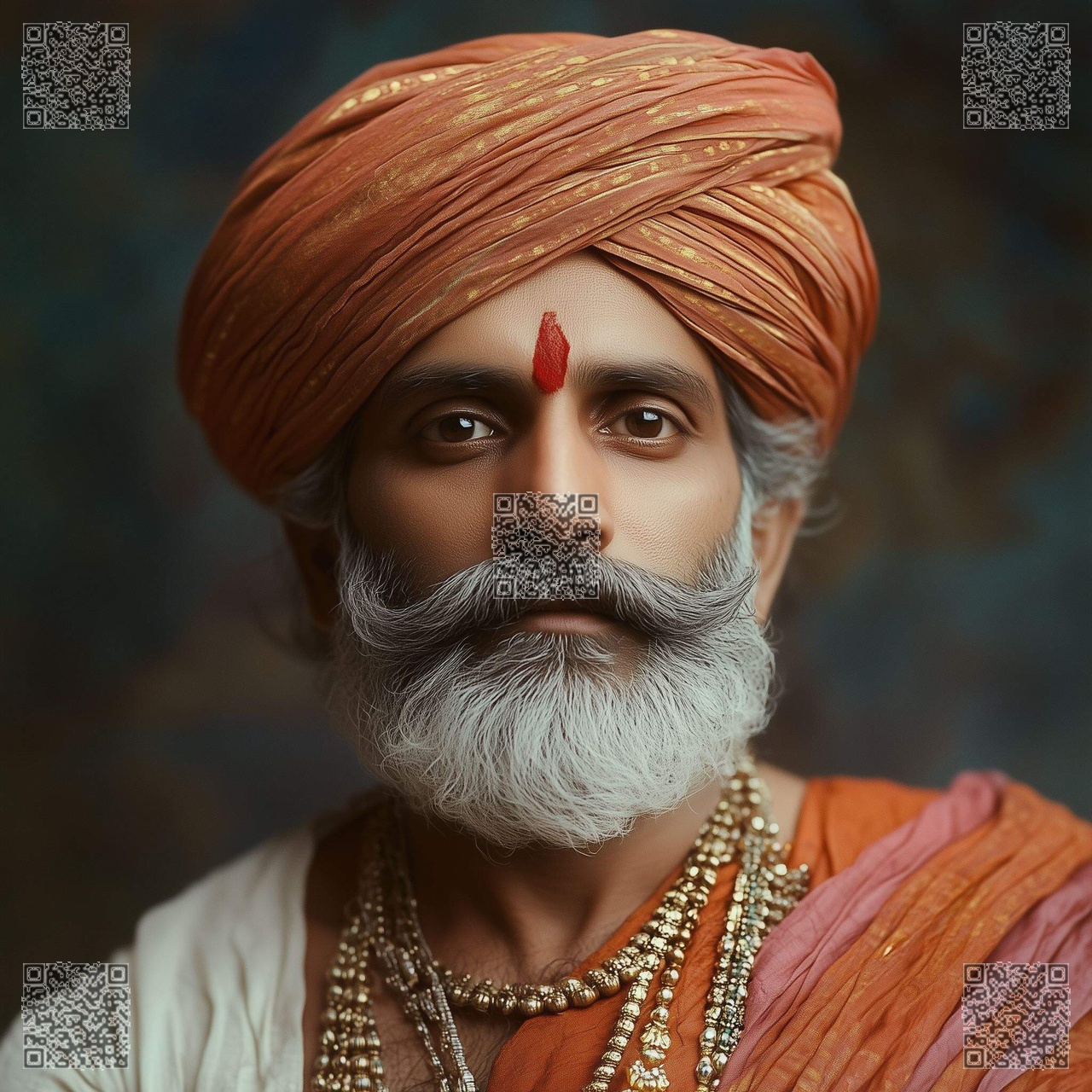

The early 20th century was a transformative period for Travancore, marked by significant political reforms and cultural preservation. During this time, two remarkable individuals—Kochu Kunju Channar, the revered patriarch of the Alummoottil Tharavad, and M. Krishnan Nair, the visionary Diwan of Travancore (1914–1920)—developed a deep and mutually enriching relationship that left an indelible mark on the region’s history.

Their bond began in 1914, shortly after Nair’s appointment as Diwan. Aware of Channar’s influence in Alappuzha, Nair made a formal visit to the Alummoottil Tharavad. The grand reception Channar hosted showcased not only the magnificence of traditional Kerala hospitality but also his keen understanding of local governance. Nair, deeply impressed, found in Channar a wealth of practical knowledge about maintaining harmony in a diverse society.

The relationship soon evolved into collaboration. In 1915, when a land dispute involving farmers threatened to disrupt the peace, Nair personally sought Channar’s assistance in mediating the conflict. Known for his fairness, Channar helped resolve the issue amicably, earning Nair’s trust. Around the same time, the two began discussing education reform, and Channar’s proposal for a school in Alappuzha aligned perfectly with Nair’s progressive vision. The Diwan allocated funds to make the idea a reality, marking one of their first joint achievements.

Their collaboration extended beyond governance. During Onam celebrations in 1917, Channar invited Nair to partake in the grand festivities at the Alummoottil Tharavad. This event, steeped in tradition, allowed Nair to witness Kerala’s rich cultural heritage firsthand. The Diwan, who often had to reconcile British-imposed policies with local customs, found solace in Channar’s ability to balance modernity with tradition.

However, their relationship wasn’t without spirited debates. In 1918, Channar, a staunch critic of British interference, voiced his concerns about increasing taxation under colonial rule. Nair, tasked with implementing policies that aligned Travancore with British expectations, engaged in a thoughtful exchange with Channar. While they held differing views, their mutual respect deepened.

Their partnership also proved invaluable during crises. In 1918, devastating floods wreaked havoc in Alappuzha. Nair, overseeing the relief efforts, turned to Channar for help in mobilizing local resources. Channar’s swift action ensured food and shelter for affected families, cementing his reputation as a leader who transcended familial boundaries.

Preserving heritage was another shared passion. In 1919, Channar approached Nair with a proposal to protect Kerala’s traditional tharavad houses, many of which were falling into disrepair. Nair, recognizing their cultural significance, implemented policies to safeguard these historical structures, with Alummoottil serving as a prime example.

As Nair’s tenure drew to a close in 1920, Channar invited him to a farewell dinner at the Alummoottil Tharavad. In an emotional gesture, Channar presented Nair with a handcrafted ivory artifact, symbolizing their shared dedication to Travancore’s prosperity.

This extraordinary partnership between Kochu Kunju Channar and M. Krishnan Nair bridged tradition and progress, showcasing how mutual respect and collaboration can shape history. Though separated by age and background, their shared vision for a harmonious and prosperous Travancore continues to inspire generations.